Resilience in a riskier world

Society

Armida

Salsiah Alisjahbana

Ulaanbaatar /MONTSAME/. Over the past two decades, the Asia-Pacific region has made remarkable

progress in managing disaster risk. But countries can never let down their

guard. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its epicentre now in Asia, and all its

tragic consequences, has exposed the frailties of human societies in the face

of powerful natural forces. As of mid-August 2021, Asian and Pacific countries

had reported 65 million confirmed coronavirus cases and more than 1 million

deaths. This is compounded by the extreme climate events which are affecting the

entire world. Despite the varying contexts across geographic zones, the climate

change connection is evident as floods swept across parts of China, India and Western

Europe, while heatwaves and fires raged in parts of North America, Southern

Europe and Asia.

The human and economic impacts of

disasters, including biological ones, and climate change are documented in our 2021

Asia-Pacific Disaster Report. It demonstrates that climate change is

increasing the risk of extreme events like heatwaves, heavy rain and flooding,

drought, tropical cyclones and wildfires. Heatwaves and related biological

hazards in particular are expected to increase in East and North-East Asia while

South and South-West Asia will encounter intensifying floods and related

diseases. However, over recent, decades fewer people have been dying as a

result of other natural hazards such as cyclones or floods. This is partly a

consequence of more robust early warning systems and of responsive protection but

also because governments have started to appreciate the importance of dealing

with disaster risk in an integrated fashion rather than just responding on a

hazard-by-hazard basis.

Nevertheless, there is still much more

to be done. As the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated, most countries are still

ill-prepared for multiple overlapping crises – which often cascade, with one

triggering another. Tropical cyclones, for example, can lead to floods,

which lead to disease, which exacerbates poverty. In five hotspots around the region

where people are at greatest risk, the human and economic devastation as these

shocks intersect and interact highlights the dangers of the poor living in several

of the region’s extensive river basins.

Disasters threaten not just human lives

but also livelihoods. And they are likely to be even more costly in future as

their impacts are exacerbated by climate change. Annual losses from both natural

and biological hazards across Asia and the Pacific are estimated at around $780

billion. In a worst-case climate change scenario, the annual economic losses

arising from these cascading risks could rise to $1.3 trillion – equivalent to

4.2 per cent of regional GDP.

Rather than regarding the human and

economic costs as inevitable, countries would do far better to ensure that

their populations and their infrastructure were more resilient. This would

involve strengthening infrastructure such as bridges and roads, as well as

schools and other buildings that provide shelter and support at times of

crisis. Above all, governments should invest in more robust health

infrastructure. This would need substantial resources. The annual cost of

adaptation for natural and other biological hazards under the worst-case

climate change scenario is estimated at $270 billion. Nevertheless, at only one-fifth

of estimated annualized losses – or 0.85 per cent of the Asia-Pacific GDP, it’s

affordable.

Where can additional funds come from?

Some could come from normal fiscal revenues. Governments can also look to new,

innovative sources of finance, such as climate resilience bonds,

debt-for-resilience swaps and debt relief initiatives.

COVID-19 has demonstrated yet again how all disaster

risks interconnect – how a public health crisis can rapidly trigger an economic

disaster and societal upheaval. This is what is meant by “systemic risk,” and

this is the kind of risk that policymakers now need to address if they are to

protect their poorest people.

This does not simply mean responding rapidly with

relief packages but anticipating emergencies and creating robust systems of

social protection that will make vulnerable communities safer and more

resilient. Fortunately, as the Report illustrates, new technology, often

exploiting the ubiquity of mobile phones, is presenting more opportunities to

connect people and communities with financial and other forms of support. To

better identify, understand and interrupt the transmission mechanisms of

COVID-19, countries have turned to “frontier technologies” such as artificial

intelligence and the manipulation of big data. They have also used advanced

modelling techniques for early detection, rapid diagnosis and containment.

Asia

and the Pacific is an immense and diverse region. The disaster risks in the

steppes of Central Asia are very different from those of the small island

states in the Pacific. What all countries should have in common, however, are

sound principles for managing disaster risks in a more coherent and systematic

way – principles that are applied with political commitment and strong regional

and subregional collaboration.

------------------

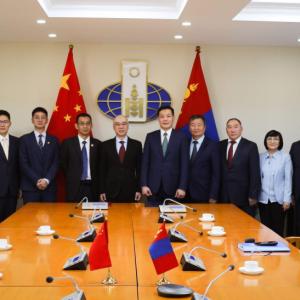

Ms. Armida Salsiah Alisjahbana is the United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific (ESCAP)

Улаанбаатар

Улаанбаатар