Countries are scrambling for vaccines. Mongolia has plenty.

Society

By playing off its big

neighbors, Russia and China, Mongolia has emerged as a positive outlier among

developing nations on the hunt for shots.

Mongolia, a country of grassy hills, vast deserts and

endless skies, has a population not much bigger than Chicago’s. The small

democratic nation is used to living in the shadow of its powerful

neighbors, Russia and China.

But during

a pandemic, being a small nation sandwiched between two vaccine makers with

global ambitions can have advantages.

At a time when most

countries are scrambling for coronavirus vaccines, Mongolia now has enough

to fully vaccinate its entire adult population, in large part thanks to deals

with both China and Russia. Officials are so confident about the nation’s

vaccine riches that they are promising citizens a “Covid-free summer.”

Mongolia’s success in procuring the vaccines in the span of

a few months is a big victory for a low-income, developing nation. Many poor

countries have been waiting in line for shots, hoping for the best. But

Mongolia, using its status as a small geopolitical player between Russia and

China, was able to snap up doses at a clip similar

to that of much wealthier countries.

“It speaks to the Mongolian ability to play to the two great

powers and maximize their benefits even while they are on this tightrope

between these two countries,” said Theresa Fallon, director of the Center for

Russia Europe Asia Studies in Brussels.

It is also a win for China and Russia, which have extensive

resource interests in Mongolia and ambitions to appear to play a role in ending

the pandemic, even when much of the world has expressed deep

skepticism over their homegrown

vaccines.

Mongolia is a buffer between eastern Russia, which is

resource rich and mostly unpopulated, and China, which is crowded and hungry

for resources. While Russia and China are often aligned on the global stage,

they have a

history of conflict and are wary of each others’ interests in

Mongolia. Those suspicions can be seen in their vaccine diplomacy.

In Ulaanbaatar, the capital, 97 percent of the

adult population has received a first dose and more than half are fully

vaccinated, according to government statistics.

In Ulaanbaatar, the capital, 97 percent of the

adult population has received a first dose and more than half are fully

vaccinated, according to government statistics.

“Putin is deeply concerned about what China is doing in

their neighborhood,” Ms. Fallon said of Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin.

Russia has sold Mongolia one million doses of its Sputnik V vaccine. China has provided four million doses of vaccine — the final shipment of doses arrived this week. Mongolia’s most recent agreement with China’s Sinopharm Group, which is state-owned, was made days before the company received emergency authorization from the World Health Organization.

Mongolia was late to the global clamber for Covid-19

vaccines. For nearly a year officials boasted that there were no local cases.

Then came an outbreak in November. Two months later, political

crisis precipitated by the mishandling of the virus led to the sudden

resignation of the prime minister. The prospect of continued coronavirus

restrictions threatened to throw the country into further political turmoil.

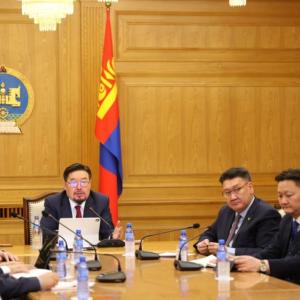

The new prime minister, Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai, pledged

to restart the economy, which had suffered from lockdowns and border closures,

particularly in the south, where Mongolian truck drivers ferry coal across the

border to China’s steel mills. But these plans were complicated by surging

cases, with the daily count going from hundreds a day to thousands.

“We were quite desperate,” said Bolormaa Enkhbat, an

economic and development policy adviser to Mr. Luvsannamsrai.

The new prime minister pledged to restart the economy, which suffered from coronavirus lockdowns. Khasar Sandag for The New York Times

Mongolia approached China and Russia first, the foreign

minister said, hoping longstanding economic ties with each country would help

move it to the front of the line of countries seeking vaccines. Officials

simultaneously explored diplomatic and private channels — putting in requests

for donations from rich countries and the world’s biggest vaccine

manufacturers.

They contacted price-gouging middlemen, international health

organizations and vaccine alliances for poorer countries. One intermediary

offered to sell Pfizer-BioNTech’s Covid vaccine for $120 a shot, nearly a

quarter of the average monthly salary, Ms. Enkhbat said. Covax, the global

vaccine-sharing alliance, which Mongolia signed onto in July 2020, promised

doses in the fall or winter.

With each breakthrough from Russia, negotiations moved more

quickly with China.

In early February, Mongolia approved Russia’s Sputnik V

vaccine. Three days later, China’s Sinopharm Group received approval for

its Vero Cell vaccine. Soon after, China donated 300,000 doses

of its Sinopharm vaccine to Mongolia, citing a “profound traditional friendship” as motivation.

Opening up more of the border between China and Mongolia was

also a part of the vaccine discussions, Chinese and Mongolian officials said in

Chinese state media. Mongolia needs China to buy its coal — exports to the

country make up nearly a quarter of Mongolia’s annual economic growth. The

revenues helped to pad Mongolia’s budget by a quarter last year.

After a month of back and forth, the Mongolian government struck a deal in March with Russia’s Gamaleya Research Institute, too, for one million doses of the Sputnik vaccine. Days later, Mongolia finalized an agreement to buy 330,000 additional doses of the Sinopharm vaccine.

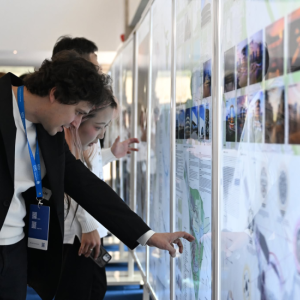

Officials are so confident about Mongolia’s

vaccine riches that they are promising citizens a “Covid-free summer.” Khasar Sandag

for The New York Times

Officials are so confident about Mongolia’s

vaccine riches that they are promising citizens a “Covid-free summer.” Khasar Sandag

for The New York Times

When there was a last-minute hitch in the delivery of the

purchased Chinese vaccines, a call on April 7 between China’s premier, Li

Keqiang, and Mongolia’s prime minister, Mr. Luvsannamsrai, helped to smooth

things over and reassure both sides. Up to that point, it was still unclear if

Mongolia would be able to rely on China or if it would need to return to Russia

for more vaccines.

“That’s what paved the way for the rest of the deal,” Ms.

Enkhbat said about the phone call, Mr. Luvsannamsrai’s first with Mr. Li. “We

laid out the situation and said that we are betting on Chinese vaccines at a

time when the rest of the world fully isn’t.”

Mongolia has also secured commitments from AstraZeneca and

Pfizer-BioNTech. So far it has received only 60,000 of the Sputnik vaccine

because of manufacturing delays. But the Chinese vaccine will account for a majority

of Covid-19 shots for Mongolia’s population.

“We are thankful to our partners, especially China, that

they are providing us with vaccinations when they also need it for domestic

use,” said Battsetseg Batmunkh, Mongolia’s foreign minister.

The Chinese and Russian embassies in Mongolia did not

respond to requests for comment.

In Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital, 97 percent of the adult population has received a first dose and more than half are fully vaccinated, according to government statistics. Across the country, more than three quarters of Mongolians have already received one shot.

Coal exports to China make up nearly a quarter of

Mongolia’s annual economic growth. Gilles Sabrie for The New

York Times

Coal exports to China make up nearly a quarter of

Mongolia’s annual economic growth. Gilles Sabrie for The New

York Times

The country’s vaccination effort still faces hurdles.

Mongolia is economically dependent on China, and many of its citizens continue

to fear its power and influence. When tensions have arisen in the past, China

has shut its border and stopped purchasing Mongolian coal.

Mongolians have also expressed a preference for Russia’s

Sputnik vaccine. To get the population to take the Sinopharm shot, the

government has offered each citizen 50,000 tugriks — about $18 — to get fully

vaccinated. The average monthly salary in 2020

was $460.

The terms and pricing of the Sinopharm and Sputnik deals

were not made public, and Mongolia’s foreign ministry declined to comment on

pricing. Representatives for the Gamaleya Research Institute and Sinopharm did

not respond to requests for comment.

While some global health experts have questioned whether

Sinopharm will be able to continue to deliver on its commitments overseas, it

has delivered all of the doses Mongolia ordered. China has said it can make as

many as five billion doses by the end of the year, though officials have warned

that the country is struggling to make enough shots for its citizens.

There are also some signs that governments that have chosen

the Sinopharm vaccine may have to roll out a

third booster shot sooner than expected.

China, for its part, may be playing a long game, said Julian

Dierkes, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia who

specializes in Mongolian politics. Though many Mongolians may still not trust

China, the Mongolian government will remember how it made its vaccines

available at a critical moment.

“We could coin a phrase here: ‘The opportunity of

smallness,’” he said.

Source: Alexandra

Stevenson, The New York Times

Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar