Emperor's Dining Table Revives Korea's Royal Cuisine and Diplomatic Legacy

Society

Seoul, May 22, 2025 /MONTSAME/. In the serene courtyards of Deoksugung Palace in central Seoul, once home to Korea’s last royals, an event titled “The Emperor’s Dining Table” welcomed international guests to experience the elegance and symbolism of royal cuisine. Hosted by the Royal Palaces and Tombs Center of the Korea Heritage Service and the Korea Heritage Agency, the program revived a moment from 1905, when Emperor Gojong, the last reigning monarch of the Korean Empire, held a state luncheon for Alice Roosevelt, daughter of the 26th U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

The original luncheon, held on September 20, 1905, was no ordinary gesture of hospitality. At the time, Korea had declared itself an empire in 1897 in a bid to affirm independence from encroaching foreign powers. Under Gojong’s rule, the country had launched a series of modernization efforts known as the Gwangmu Reforms, including urban development, military strengthening, legal modernization, and national infrastructure projects. Yet amid rising geopolitical pressure, Korea’s sovereignty remained precarious.

In this context, Emperor Gojong’s decision to serve Alice Roosevelt a table of traditional Korean royal dishes, rather than the expected Western fare, was an act of resistance and cultural diplomacy.

At this year’s Deoksugung event, that message came vividly to life. Guests sampled dishes recreated from the imperial menu while cultural experts explained their origins, preparation, and symbolic meaning. Each element revealed how royal cuisine functioned as both sustenance and statement, rooted in the land, shaped by seasonal rhythms, and designed to express dignity and harmony.

The main course featured a selection of elegantly prepared dishes, each with distinctive ingredients central to Korean food culture.

- Goldongmyeon, a delicate noodle dish layered with vegetables, egg garnish, and beef, known as ‘straightening the bones’ due to its appetite-boosting effect, was once served to royalty as a symbol of harmony. Its ingredients represent the five cardinal colors of Korean philosophy - blue (green), red, yellow, white, and black - believed to promote balance within the body.

- Jangkimchi, a mild water kimchi seasoned with soy sauce, highlighted a milder, more refined taste. Made with cabbage and radish, this style reflects the emphasis on subtle flavor and seasonal vegetables in traditional Korean homes, especially during warmer months.

- Hwayangjeok, presented ingredients such as beef, mushroom, egg, and vegetables neatly arranged on skewers by color. More than decoration, the color arrangement reflects obangsaek, the traditional color spectrum that connects food to health, direction, and spiritual balance.

- Jeonbokcho, a dish of abalone slices simmered in soy-based sauce, was prized in royal courts for its rarity and health benefits. Abalone, known for strengthening stamina and restoring energy, was often served to important guests.

- Jenyueo, thinly sliced white fish coated in flour and egg, showcased the light and precise cooking techniques valued in court cuisine.

- The savory Pyeonyuk, sliced boiled beef brisket, was served alongside Chojang, a tangy dipping sauce made of soy sauce and vinegar.

Dessert sustained the theme of seasonal harmony and digestive ease.

Dessert sustained the theme of seasonal harmony and digestive ease.

- Wonsobyeong, small glutinous rice balls floating in sweetened water, provided a gentle and comforting end to the meal. Glutinous rice is believed to warm the body and promote energy, while the honey water aids digestion.

- Saengyi (pear) and grapes, as well as Jeonggwa, vegetables like lotus root or bellflower root simmered in honey, were a classic preserved sweet in royal households. Lotus root is associated with purity and calm, while bellflower is known for respiratory health.

Beyond the elegant tableware and ceremonial arrangements, the experience offered a thoughtful meditation on the many forms diplomacy can take - among them, the quiet assertion of cultural identity through food. Contrary to popular belief that Korea’s royal court catered to Western palates, the 1905 luncheon and its modern recreation challenge this narrative. Instead, it highlights the deliberate resolve and cultural confidence of a nation that once stood its ground by serving its own cuisine proudly to global guests.

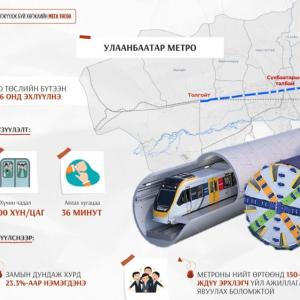

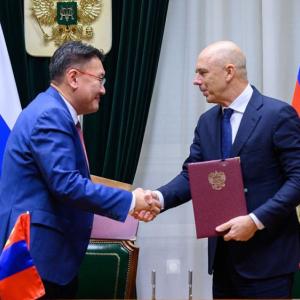

Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar